On Wednesday, US Vice-President JD Vance is hosting talks at the White House with the foreign ministers of Denmark and Greenland, alongside US Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

At the centre of the discussions is the future of Greenland, the world’s largest island, which has suddenly become a focal point of international tension.

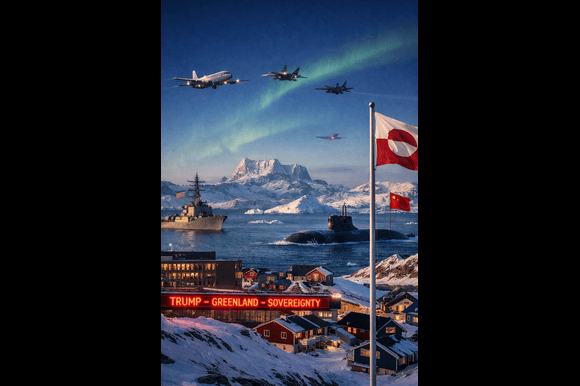

In Nuuk, Greenland’s snow-covered capital, a large digital ticker scrolls continuously above a shopping centre. Even without understanding the Greenlandic language, the message is unmistakable: the words “Trump,” “Greenland,” and “sovereignty” flash repeatedly in bright red letters.

President Donald Trump has made no secret of his intentions. He has said he wants Greenland and will acquire it “the easy way or the hard way”. Ahead of the talks, Trump repeated his argument that the US requires Greenland for national security and insisted that Nato “should be leading the way” to secure American control.

Following Trump’s recent controversial use of military force in Venezuela, many Greenlanders are taking his remarks seriously. The days leading up to the Washington meeting have been filled with anxiety, with residents describing the wait as agonising.

“It feels like this has been going on for years,” several passers-by told me.

“I would urge Donald Trump to use both ears, listen more and talk less,” said Amelie Zeeb, pulling off her thick sealskin mittens known locally as pualuuk so she could gesture emphatically. “We are not for sale. Our country is not for sale.”

Inuit writer and musician Sivnîssoq Rask echoed that sentiment. “My hope is that our country can become independent and well governed not something that can be bought,” she said.

Maria, cradling her seven-week-old baby inside her winter coat, voiced a more personal fear. “I worry about my child’s future. We don’t want all this attention here,” she said.

Despite those concerns, global interest in Greenland is unlikely to fade. The stakes extend far beyond the island itself, as the dispute increasingly pits two Nato allies Denmark and the United States — against each other.

Greenland is a semi-autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has warned that any attempt by the US to seize the island by force would effectively end the transatlantic defence alliance that Europe has depended on for decades.

Such a move would also further damage US-European relations, already strained since Trump returned to the White House. European leaders, meanwhile, are eager to keep the Trump administration engaged particularly to secure continued US support for a lasting peace agreement in Ukraine.

The consequences of a breakdown over Greenland could therefore be far-reaching. Yet it remains unclear what tone Washington will adopt during Wednesday’s talks. Will compromise prevail, or will confrontation dominate?

Trump insists Greenland is essential to US security, repeatedly claiming that without American control, China or Russia will move in. In response, major European powers which have openly backed Danish sovereignty are scrambling to present alternative security solutions that would strengthen Nato’s presence in the Arctic.

The UK and Germany are said to be leading these efforts, while France announced on Wednesday that it would open a consulate in Greenland early next month. French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot described the move as a “political signal” demonstrating France’s increased engagement in what he called “this territory of the Kingdom of Denmark”.

German Chancellor Friedrich Merz acknowledged shared concerns with Washington. “We agree that this part of Denmark needs stronger protection,” he said on Monday. “Our goal is to improve Greenland’s security together.”

Patrick Sensburg, chairman of the German Reservists Association, has gone further, calling for at least one European brigade to be stationed in Greenland as soon as possible. He argued that Germany would carry “special responsibility” in such an effort and said training troops in Arctic conditions would bring long-term strategic benefits.

The UK government is also holding discussions with European allies about possible troop deployments to Greenland, particularly in response to perceived threats from Russia and China.

So far, Nato discussions remain at an early stage. While no troop numbers have been set, proposals under consideration include the deployment of soldiers, naval vessels, aircraft, submarines and counter-drone systems.

One concrete idea is the creation of a maritime Nato “Arctic Sentry”, modelled on the “Baltic Sentry” mission launched after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Both regions contain extensive underwater infrastructure, including energy pipelines and internet cables that underpin global communications and financial transactions all vulnerable to hybrid attacks.

“There is far more that can be done in the Arctic,” said Oana Lungescu, Nato’s longest-serving spokesperson until 2023 and now a distinguished fellow at the RUSI defence think-tank.

“I don’t expect the UK or Germany to deploy large numbers of troops to Greenland,” she said. “But they could expand exercises or hold more regular drills. Nato has already begun deploying maritime assets for Cold Response, the large biannual Norwegian-led exercise in the High North. The Arctic became a strategic priority after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine but more action is still needed.”

Even before any additional forces arrive, Denmark on Wednesday sent a contingent of military personnel to Greenland to “prepare for their arrival”, according to Danish television just hours before talks in Washington were due to begin.

Greenland occupies a crucial position between the US and Canada on one side, and Russia and Europe on the other.

Its strategic importance was first fully recognised by Washington during the Second World War, when the US occupied the island to prevent it falling into Nazi hands following Germany’s invasion of Denmark. After the war, the US attempted to buy Greenland, but Copenhagen refused. Shortly afterwards, both nations became founding members of Nato, and in 1951 signed a defence agreement that still allows the US to maintain bases and deploy troops on the island.

Greenland lies along the shortest route between the continental US and Russia, making it vital for missile defence. Although Washington sharply reduced its presence after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it retained the Pituffik Space Base one of its most important radar installations.

The surrounding waters are equally significant. The GIUK gap between Greenland, Iceland and the UK is a key maritime choke point used to monitor Russian and Chinese naval movements, particularly submarines transitioning between the Arctic and the Atlantic.

The US has urged Denmark to strengthen surveillance capabilities, and Copenhagen recently committed $4bn to Greenland’s security. The Trump administration, however, has downplayed the move.

Whether Nato’s proposed security enhancements will satisfy Washington remains uncertain.

Julianne Smith, the former US ambassador to Nato and now president of Clarion Strategies, said the meeting could prove decisive.

“This is a critical moment,” she said. “Denmark and Greenland are taking it extremely seriously. The question is whether any of these proposals will satisfy a White House that appears more focused on expanding US territory than addressing Greenland’s security needs.”

Some analysts question whether security is really the primary concern. Ian Lesser of the German Marshall Fund argues that the Pacific High North is far more sensitive for US defence than Greenland, where Russian and American interests directly overlap near the Bering Strait.

Tensions in that region have risen sharply since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with frequent interceptions of Russian military aircraft by US and Canadian fighter jets.

Lesser believes Trump’s fixation on Greenland points more towards economic interests than traditional security. Greenland holds vast reserves of rare earth minerals and other resources essential to high-tech and defence industries, and the melting Arctic ice is opening new shipping routes that could prove highly lucrative.

Both security and economic concerns, he argues, could be addressed without challenging Danish or Greenlandic sovereignty through Nato cooperation and negotiated investment agreements.

Yet Trump’s rhetoric suggests little appetite for compromise.

“We’re talking about acquiring, not leasing,” he said earlier this week. “You need ownership. You need title.”

Greenland may be politically European but geographically North American closer to Washington than Copenhagen. While many Greenlanders favour eventual independence from Denmark, opinion polls show around 85% reject becoming part of the United States.

Ahead of the talks, Greenlandic Prime Minister Jens-Frederik Nielsen described the situation as a geopolitical crisis, stating: “If we have to choose between the US and Denmark here and now, we choose Denmark.”

Ultimately, however, the outcome may hinge on Trump himself. “He’s unpredictable,” said Sara Olvig of Greenland’s Centre for Foreign and Security Policy. “If Greenland is taken by coercion, the US will no longer be the land of the free. It would mark the end of Nato and the democratic world as we know it.”

Russia and China will be watching Wednesday’s meeting closely almost as closely as Greenlanders themselves. The stakes could hardly be higher.