The skull of a Malagasy monarch killed during France’s colonial conquest has been formally repatriated to Madagascar, more than a century after it was taken to Paris.

At a solemn ceremony at France’s culture ministry, officials handed over the remains of King Toera of the Menabé kingdom—along with the skulls of two members of his court—to Madagascar’s representatives.

The remains had been transported to France in the late 19th Century and placed in the collections of the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Their return marks the first application of a new French law designed to accelerate the restitution of human remains acquired under colonial rule.

“These skulls entered our national collections in circumstances that flagrantly violated human dignity and in the context of colonial violence,” French Culture Minister Rachida Dati said during the ceremony, according to AFP.

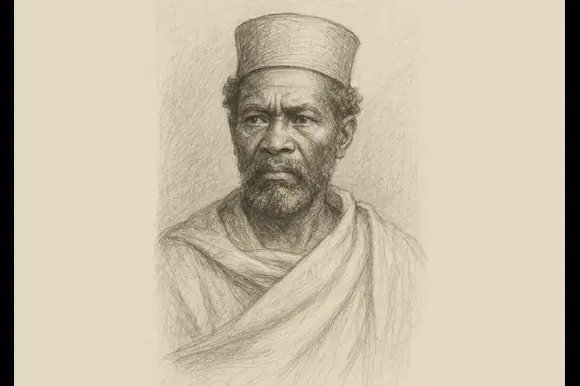

In August 1897, French forces launched an assault to impose colonial authority over the Menabé kingdom of the Sakalava people in western Madagascar, massacring its defenders. King Toera was killed and decapitated, and his head sent to Paris where it was archived for study.

For nearly 130 years, Malagasy descendants of the king, supported by their government, campaigned for the return of the remains. Pressure from both family and state finally led to their restitution.

Although scientific tests carried out some years ago could not definitively prove the skull belonged to King Toera, the identification was ultimately confirmed by a traditional Sakalava spirit medium, whose recognition was accepted by the Malagasy authorities.

Speaking at the handover, Madagascar’s Culture Minister Volamiranty Donna Mara described the return as a deeply meaningful act. “Their absence has been, for more than a century, an open wound in the heart of our island,” she said.

This is not the first time France has restored human remains taken during the colonial period. One of the most high-profile restitutions came in 2012, when the body of Saartjie Baartman—derisively known as the “Hottentot Venus”—was finally repatriated to South Africa after years on display in Europe.

But unlike earlier cases, this handover is the first carried out under a new law specifically designed to ease the process of returning remains.

The Museum of Natural History alone is believed to house over 20,000 human remains collected worldwide under the guise of scientific study, many acquired in contexts of coercion and violence.