Human Rights Violation in Rohingya and Role of International Community

Four years after the 2012 violence in Rakhine State, some 120,000 Muslims Rohingya still live in IDP camps. There is also an alarming increase in incitement to hatred and religious intolerance by ultra-nationalist Buddhist organizations. The report finds that these violations against the Rohingya may constitute crimes against humanity.

Myanmar, dominated by Buddhists, has a long history of discrimination and persecution against Muslims. The Burmese government denies full citizenship to Muslims and regards them as undocumented migrants from Bangladesh, while the international community and human rights groups reject such arguments, asserting that the Muslim minority has historical roots in Burma’s territory.

The formation of a new government led by civilians did not translate into significant improvements in the human rights situation. Acts of violence and discrimination against the persecuted Rohingya minority increased. Religious intolerance and anti-Muslim sentiment intensified. In the north of the country, clashes between the army and ethnic armed groups escalated. The government tightened access restrictions for the UN and other humanitarian agencies to displaced communities.

Thousands of Rohingya refugee ships from Myanmar have sought asylum in the neighboring countries of Southeast Asia, but these countries have sent them all back for help elsewhere. The Government of Myanmar has refused to recognize the Rohingyas as an ethnic group and considers them to be illegal migrants. Most Rohingyas are Muslim and live on the border of Myanmar and Bangladesh.

To escape the persecution of the military-led government, many Rohingyas crossed borders to seek refuge and work in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia. Some have been victims of human trafficking groups.

The Malaysian government has denied that it has not provided humanitarian aid to the Rohingyas despite its lack of support in the area of refugee protection. According to Human Rights Watch, neighboring Indonesia admitted pushing an overcrowded boat of refugees and directed them to Malaysia. More or less, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia are making things worse by their heartless policies of pushing back this new wave of ‘boat people’ and endangering the lives of thousands of people.

The crisis of migrants drifting on the sea off Thailand and Malaysia provokes a regional discord in Southeast Asia. Burma, where most of these migrants come from, Muslim Rohingya, threatens to boycott a regional meeting. Thailand reacted by calling on international organizations to rescue, notably to open temporary refugee camps.

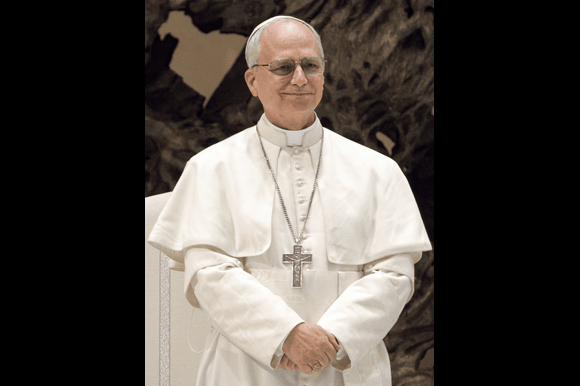

In recent months, international pressure has increased over Myanmar to give more rights to the Rohingyas, but Aung San Suu Kyi, the country’s top Nobel Peace Prize winner, has hitherto held a hard line. Even Pope Francis, who will visit Myanmar and Bangladesh in November, expressed his solidarity. Last Sunday, from the Vatican, he called for respect for human rights “of the Rohingyas brothers.”

Violent clashes between the Myanmar Army and the Rohingya Muslim minority living in the west of the country

A wave of attacks on several police posts by Fighters of this ethnic group and the subsequent reaction of security forces have left more than a hundred dead in the last four days. This is the bloodiest clash of recent years, which began just hours after the UN warned the country’s authorities of the possibility of radicalization of the group, persecuted in a country with a 90% Buddhist population, if not solve your situation.

The latest clashes have occurred in the state of Rakhine, which borders Bangladesh, where about one million people live in this ethnic group. On Friday, a group of about 150 men attacked a dozen police stations with knives and homemade explosives, according to the Burmese Army. Since then, clashes have been concentrated in remote villages near the border with Bangladesh between the Burmese army and the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), which accuse each other of atrocities and human rights violations on the civilian population.

Thousands of people, about 5,000 according to the Human Rights Watch (HRW), have crossed in recent days the river that separates Myanmar from Bangladesh to escape the violence. From the neighboring country, however, the order is not to let them pass and hundreds of civilians crowd at the border. We believe that the army sweep of the villages housing the insurgents will expand and intensify in the coming days, which will exacerbate the situation.

A good part of the Rohingya lives in crowded and subhuman conditions in camps of displaced persons, without freedom of movement and with their private fundamental rights, because neither Burma nor Bangladesh recognizes them as citizens of their country. Their confinement was intensified in 2012, following an episode of violence similar to the current one that caused at least 160 deaths. UN World Food Program warned that there are more than 80,000 Rohingya children on the brink of famine in Rakhine.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Rohingya crisis is one of the longest in the world and one of the most neglected. That is why in December of last year the UN passed a resolution urging Myanmar to give Rohingyas access to citizenship, most of which are classified as stateless.

The Rohingya people have become a symbol of human rights violations. Persecuted in Myanmar and expelled on their flight to Bangladesh, the Burmese authorities use law and force to oppress this ethnic-religious community. In the country, the predominance of one ethnic group over the other, emphasizing their differences, has made a dynamic of constant repression. Saving the distances, this situation may remember one of the Tamils in Sri Lanka.

The UN influence on Myanmar is in “serious decline” after a team was prevented from accessing Rakhine state to investigate abuses committed by the army and by the Buddhist majority against the Rohingya ethnic minority. According to the sources, it is now clear that the delegation’s visit to the country in May was disastrous after the government, led in the shadows by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, prevented the team from accessing the state. The delegation’s trip, led by Miroslav Jenca on behalf of the Secretary-General António Guterres, followed the announcement that the head of the UN’s permanent mission in Myanmar was to be removed from office.